Throughout history, investors have discovered numerous ways to accidentally increase risk and reduce returns in portfolios. When people think about the acts that lead to long‐term poor performance, the two most common are panicking in or out of a market, or buying very aggressive cult‐like investments that later implode. However, a third, and many times more damaging act is when investors shift funds into asset classes that have recently outperformed. This regularly damages portfolio returns and increases risk.

The cycle tends to repeat itself over time. An asset class becomes the performance leader after 4‐5 years, and investors chase the recent intermediate‐term performance, causing the asset class to become overvalued. The overvaluation typically coincides with the slowing of the recent strong fundamental growth, or the variables which aided the outperformance. Once the overvaluation, slowing fundamentals, or reversal of positive variables sets in, the result is usually a period of strong underperformance for the asset class that everyone recently stampeded toward.

Over the recent decades, there are a number of examples of this phenomenon. Investors piled into real estate stocks after the 2000‐2006 outperformance, and bought natural resources after the 2002‐2007 strong return period. After these periods of outperformance, both asset classes underperformed as real estate stocks lost over 52% of their value over subsequent two years, and natural resources delivered negative annualized returns for the last decade. However, maybe the most interesting example has been the shift between U.S. stocks and foreign stocks over the last twenty years.

First, during the five year period from 1997 to 2001, U.S. stocks outpaced foreign stocks by a wide margin as seen in the table below. Internet and biotechnology stocks were hot, interest rates were falling, and the dollar was strong. As the outperformance of U.S. stocks continued, more and more assets shifted from foreign stocks to U.S. stocks. Soon after the asset flows peaked, U.S. stocks began a period of major underperformance in which foreign stocks outperformed the U.S. by 77% over five years. Ironically when the decade period from 1997‐2006 was complete, the annualized returns were nearly identical.

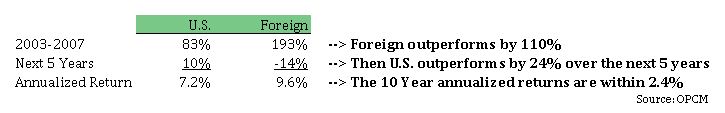

Next, as the dollar fell and valuations were lower in foreign stocks, they began to outperform in 2003. Foreign earnings growth was slightly higher, plus the foreign markets lacked the rubble of an internet implosion. From 2003-2007, foreign stocks outperformed as the dollar fell and interest rates rose. As 2007 started, investors poured greater and greater sums into foreign stocks believing the growth and variables like the dollar weakness would continue into perpetuity. However, growth slowed and many positive variables reversed. Once we entered 2008, foreign stocks proceeded to sharply underperform. Five years later, U.S. stocks had outpaced foreign by 24%, as seen below.

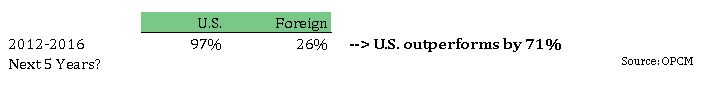

Finally, today we have witnessed the same investor bias of chasing performance after a number of years of outperformance. Since 2012, U.S. stocks have outperformed foreign stocks by 71%, as the U.S. emerged from the credit recession before the rest of the world, the dollar was strong, and interest rates fell, as seen in the following chart.

Turning to valuation, with the recent U.S. outperformance, the S&P 500 trades at about 17.5 times forward annual earnings with a price-to-book value of 2.7. Outside the U.S., mainly due to the major performance lag, foreign stocks trade at only 13.7 times earnings with a price-to-book value of 1.6. On these two valuation metrics, U.S. stocks trade at a major premium to foreign stocks (after five years of outperformance).

A final way to analyze the global equities situation is to observe how the two segments have performed compared to their average long-term annualized return.

Since the early 1970s, U.S. stocks and foreign stocks have posted similar long-term annualized returns. However, over the last five years, U.S. stocks have posted a bloated 14.5% annual return. This return is over 4.2% higher per year than the U.S. long-term average, and higher than foreign stocks by nearly 10% annually. This five-year performance difference has only occurred a few times since the early 1970s. When examining foreign stocks, the picture is nearly the inverse. Over the last five years, foreign stocks have gained only 4.7% annually. This return is 4.5% below the annual long-term average per year over the last five years.

Looking to the future, many investors assume the dollar will continue to be strong for a number of years, interest rates will only rise slowly, and all of Trump’s policies will hurt foreign companies. However, what if any of these consensus thoughts are wrong? If so, this may usher in a new outperformance period for foreign stocks.

Our message is simple. As the nearly 50% rise in the U.S. dollar begins to slow, while interest rates begin to rise, and/or the upcoming administration’s policies are not universally devastating for foreign companies, we could enter the next extended period of foreign stocks outperforming U.S. stocks. Add on the meaningful valuation discount in foreign stocks, along with negative sentiment, and the performance inflection point may arrive in 2017. Do we recommend selling all U.S. stocks? No. Do we recommend increasing foreign stock exposure for most investors? Yes. Does history indicate this move is prudent? Yes.